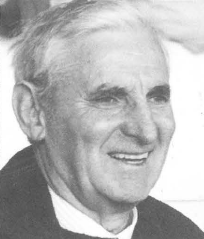

Lory Meagher (1899 - 1973)

Talk given at the Lory Meagher Museum, Tullaroan, Co. Killkenny, September 1999

‘As steel-blue clouds spread like a mourning-pall across the evening sky, hundreds - rich and poor, gentle and simple, young and old, men and women, clerics and nuns and laymen - filed through the mortuary chapel of St. Luke’s Hospital, Kilkenny for a last glimpse of all that was mortal of one of the great artists of the ash, a supreme craftsman of the caman.'

‘That the heavens themselves wept without restraint as the funeral procession wound its slow way through the narrow streets of Irishtown, old-world streets silent now, but streets that had so often re-echoed the thundering cheers of victory when the same Lory Meagher and his comrades came triumphantly home, garlanded with hurling glory.'

‘Now the only sound in those rain-swept streets came from the marching feet of the solid phalanx of All-Ireland stars who headed the cortege, the men of the Black and Amber, from Gaulstown’s 83-year old Dick Grace, who won his first All-Ireland away back in 1909, to Pa Dillon, from Freshford St. Lachtain’s, who won his last in 1972.'

‘At the boundaries of the old city of St. Canice, the hurlers split their ranks to form a guard of honour and the funeral moved on along the twisting road towards the Slieveardagh Hills to halt at last outside Clohosey’s solid farmhouse, where the men of Tullaroan were waiting, led by renowned members of two famed hurling families, Sean Clohosey and Tom Hogan. So it was, his coffin swaying on the shoulders of his old neighbours and their sons, that Lory Meagher from Curragh, the man whose name had for so long been part of hurling’s lore and legend, came home for the last time.’

So wrote Padraig Puirseal, in a tribute to Lory Meagher, entitled A Craftsman Supreme, in the 1974 edition of Our Games. Puirseal was one of the great admirers of Lory’s skill and had a fine appreciation of the man, as well as the hurler. In his appreciation of Lory in the Tullaroan history, he admitted: ‘Maybe I am prejudiced by the fact that Lory was at his greatest during my most impressionable years, but even after more than forty years since spent as a sports commentator, I have not seen the equal of his artistry, or watched a more supreme stylist. When the mood was on him Meagher was a veritable magician, with a caman for a wand; he was a wizard with the sliothar at his command.’

In fact, as a hurler, Lory has a clear record which establishes him as one of the greats of all time, but as a man he is an elusive individual, difficult to pin down, hard to define. This may be due to the evenness of his personality. Martin White, who knew him, hurled with him and played in all the All-Irelands he won, pinpointed this characteristic when talking to him last July. There were no extremes of behaviour in his make-up. He wasn’t given to outlandish attitudes or extravagant poses.

Perhaps this is the reason why much hasn’t been written about him. There is no biography, no spate of articles about the man. The occasional pieces are largely repetitive. It is as if this essentially quiet man revealed little about himself to others around him and to the friends and neighbours who knew him. In contrast with the accolades written about his hurling talent, most commentators are quiet about the man, and the personality behind the skilful exponent of the game of hurling.

Perhaps we can learn something of the man through his interests, other than hurling. He was an ardent supporter of G.A.A. ideals and proud of the family connection with the foundation of the Association at Thurles in 1884. Whereas it has never been established that his father, Henry J. Meagher, attended the foundation meeting, it is possible that he was in Thurles the day the Association was founded. There is a very definite tradition that Henry Meagher, and two other Tullaroan men, Jack Hoyne & Ned Teehan travelled to the 1884 meeting. They travelled by horse transport from Tullaroan to Thurles. Christopher Walshe, who wrote A Place of Memories, about the social, sporting, historical and political life of Tullaroan, claims that the late Jack Hoyne told him himself of their presence at Thurles on the day of the foundation meeting. Walshe adds that he doesn’t think they attended the actual meeting. There is no independent witness to their attendance and the possibility exists that the visit was mixed up with a subsequent meeting. (Frank Moloney of Nenagh confused a number of meetings and made a claim in 1906 that he was at the first meeting, whereas it is certain he wasn’t.) It is significant that Henry Meagher was not enamoured by what happened in Thurles later with the so-called Fenian split. Is it possible that he was remembering this convention rather than a visit in 1884. However, we must give him the benefit of the doubt.

Henry, whose father came from Cloneen, Co. Tipperary and who acquired land in Curragh with the break up of the Scully estate, was born in Tullaroan in 1865 and took a prominent part in public life in Kilkenny. He would have been only 19 years at the time of the foundation meeting in Hayes’s Hotel. Later he was to become a member of Kilkenny County Council and other public bodies. He was an uncompromising supporter of Charles Stewart Parnell and he courageously stood by the Chief in the North Kilkenny election of 1890. He attended Parnell’s funeral in Dublin in 1891.

To have taken the stand he did showed Henry to have a single mindedness and a good strain of moral courage. He had to stand out against the strictures of the clergy who spoke from the power of the pulpit. The following quotation is an example of how some of the clergy used their position at this time. A parish priest told his flock before an election in the early 1890’s: ‘Parnellism is a simple love of adultery and all those who profess Parnellism profess to love and admire adultery. They are an adulterous set, their leaders are open and avowed adulterers, and therefore I say to you, as parish priest, beware of these Parnellites when they enter your house, you that have wives and daughters, for they will do all they can to commit these adulteries, for their cause is not patriotism - it is adultery - and they back Parnellism because it gratifies their adultery.’ Strong stuff indeed and it took a strong man to stand up to it. Obviously Henry Meagher was made of stern stuff.

Henry was educated at St. Kieran’s College and later married Elizabeth Keoghan from Threecastles. A sister of hers was the mother of the famous Grace family, which was to garner fifteen All-Ireland medals in all. A cousin was Jack Keoghan, who won five All-Irelands with Sim Walton’s team. Jer Doheny, who captained the first All-Ireland winning team, was also a cousin. The pedigree was without doubt right.

Henry Meagher was a good friend of Tullaroan hurling. One of his fields was the practice ground where many a Tullaroan man first got the feel of the hurling stick. Even in Sim Walton’s time such was the security of tenure of the club there, that the man who learned how to win seven All-Irelands on its broad acres refers to it as ‘the sports field.’ But the provision of a practice ground was not by any means Henry’s only contribution to the club. Financially, and otherwise, he was ever there to help, and it was said of him that he never waited to be asked for aid - he was always endeavouring to assist the efforts of the little village.

Whatever the arguments for and against Henry Meagher’s attendance at Thurles on that November day, what is certain is that his sons inherited their father’s nationalist principles and sporting instincts. There were four of them in family. Lory was probably the most famous of the quartet and I shall deal with him later. Henry, who was born in 1902, was rated by the late Paddy Phelan, himself one of the outstanding half-backs in the game, as prolific a scorer as Mick Mackey. But Henry went to America in 1928 and his services were lost to Kilkenny. He married Kathleen Kirby of Carrick-on-Suir and died in 1982. He had the unique if, perhaps, doubtful distinction of having played with Mooncoin against Tullaroan in a county final. He was home on leave from the Irish Army and hadn’t been chosen on the Tullaroan side.

Willie, the first child, who was born in 1895, and Frank, who was born in 1897, played during the 1920’s. Willie was on the team beaten by Cork in the 1926 All-Ireland final. Kilkenny were offered a walk-over in that game but declined to take it. The Munster championship was delayed because of the three-match marathon between Cork and Tipperary, which Cork won. The latter were unable to meet the deadline fixed for the final. They asked Kilkenny to agree to a postponement, which was granted.

Henry Meagher had four daughters also. Kitty, Catherine, who was born in 1896, married Tom Hogan and they had two sons. One died and the surviving son, Dan, is the only male descendant of Henry’s. Elizabeth, born in 1898, became a nurse and died in 1987. Rose Angela, who was born in 1906, also became a nurse and died in 1984. Mary Agnes, who was born in 1901, married Ned Hogan and they had a daughter. She died in 1978. Willie, the oldest of the boys, married but there were no children. He inherited the home place and died in 1957 Frank became a priest, ministered in Australia, became Dean of a diocese and was buried there in 1971. Henry, as was said above, emigrated to America, married and had one daughter, Betty, who lives in New York. He won a Railway Cup medal in 1927. He died in the U.S. in 1982

Lory never married. It wasn’t that he hadn’t admirers. According to Martin White, he had a load of them. One of them was a girl called Bridie Walsh, who lived on a farm in the neighbourhood. She attended many matches with him, but they never married. She eventually married and died in Killarney in 1997. Her daughter, Dolores Daly, told me her mother spoke a lot about Lory. They were sweethearts and Lory shyly hinted marriage at one stage. But he was a very shy person and the hint never became a formal proposal. Although Bridie was very fond of him, her daughter believes she was intent on leaving the land and living in the city… She went on to marry a Tom Croke from Grawn, Ballingarry. He was a radio officer and returned to land to become the first radio officer appointed at Shannon Airport. But Bridie Walsh never lost interest in Lory. She went to many All-Irelands. She spoke to her daughter about him. She kept a picture of him in a Kilkenny team hanging on the wall. Since her death her daughter has found a small photograph of Lory among her effects. Before she died she visited the museum in Tullaroan and after her name in the visitor’s book, she wrote ‘an old sweetheart.’

Apart from his shyness, nobody has satisfactorily answered the question why he never married. The simple answer might be that he was married to hurling. It is true that some of the great hurling families shied away from marriage. One of the best examples is the Leahy family of Tipperary. There were five boys in that family and three of them remained unmarried. Johnny, the most famous and the captain of two All-Ireland winning teams, had the independence of being his own boss on a farm and never married. Neither did Paddy or Tommy.

In Lory’s case there was the added factor that he was only the second in command on the farm. Willie was the eldest and he was married in the home place. This may have inhibited him from taking the plunge. Amazingly, when Willie died in 1957 his widow and Lory lived on working the farm. Then after a number of years she decided to return to her folks and left Lory with the farm.. He might have got married then but didn’t. A reason given was his devotion to his mother. He continued to look after her for a long time. Dan Hogan recalls how he, and his late brother, Henry, used to visit Curragh to stay with his mother while Lory cycled the eight miles to Kilkenny to attend a meeting of Kilkenny County Board at the Central Hotel. Perhaps by the time of her death he believed the time had passed him by and he decided to remain a bachelor.

Lory, who was christened Lorenzo Ignatius, was born in Curragh, Tullaroan, on September 16, 1899. (This lecture was originally intended for yesterday week but I convinced Dan Hogan that a Friday would be a better date. However, September 17 coincided with a big wedding in the parish and it was deemed inappropriate to clash with it. So, we are celebrating the centenary of his birth eight days late.). An unusual christian name but one which was a tradition in the Meagher family. A grand uncle of Lory’s, he was a naval doctor, was also named Lorenzo. The tradition held that a family ancestor of that name came from Italy or Spain. He was known to all as Lory, pronounced ‘Low-ry’ in Tullaroan but ‘Lowery’ outside the parish. Some people thought initially that his name was ‘Glory’ and, of course, how right they were! The Meaghers were substantial farmers, farming about 130 acres of good land and living in a two storey, thatched, 18th century farmhouse. With his siblings Lory attended the local national school, where Danny Brennan was principal and Mrs. O’Neill was his assistant. There was a boys’ and a girls’ school under the same roof.

Christopher Walshe, already referred to, who was somewhat younger than Lory, grew up in the neighbouring townsland of Trenchardstown and had this to say about his boyhood: ‘As young boys we played hurling every evening during the summer months in a field owned by our next door neighbour and kinsman, Jackie Walshe. The farm had been divided between two brothers in an earlier generation. Jack’s name was a legend in Tullaroan and Kilkenny hurling lore. Neighbouring boys who played hurling with us were the Purcells from Killahy, the Teehan brothers from New England, all great hurlers later on, Paddy Hoyne, Matty Duggan, another character, and Dan Webster, another great hurler later on.

‘I remember Jackie Walshe would join us often with his hurley. His skill with the hurley and sliotar was always apparent. Another famous hurler who often dropped in on the evening’s hurling was the renowned Lory Meagher, who lived only a short distance away at Curragh. All us young lads at the time were in awe of his skill and control of the hurling ball. Little did we realise then that we were in the presence of one of the most famous players ever to grace a hurling field.’

The parish of Tullaroan, in which Lory grew up, is a farming community with a strong tradition of hurling. In 1988, two local farmers, Paddy Clohessy and Liam Kennedy, decided to become team selectors and name their club’s team of the century. The result - the fifteen chosen were holders of a staggering forty-five All-Ireland medals. It’s relevant to give the fifteen because many of them are household names.

Pat ‘Fox’ Maher (1)

Jack Keoghan (5) Tommy Grace (0) Jack Hoyne (2)

Dan Kennedy (6) Dick Grace (5) Paddy Phelan (4)

Lory Meagher (3) Dr. Pierse Grace (3) + 2F

Sean Clohesy (1) Henry Meagher (0) Martin White (3)

Tom Walton (1) Sim Walton (7) Jer Doheny (1)

There was no place on that team for such talent as Rev. Frank Meagher, Willie Meagher, Billy Burke of the 1939 team, John Holohan of the 1922 team, Paddy Walsh of the 1931 team, Jim Hogan, Ned Teehan, who played in six All-Irelands, or Paddy Malone, who captained Kilkenny in 1949. What I’m implying is that there was so much talent in the parish there had to be such omissions.

In such a rich hurling melieu was Lory to develop and come to manhood. From the pictures of Lory that have survived from the days of his prime, he comes across as a lean angular man. Jimmy Walsh of Hugginstown described him thus in 1973 about the time of his death: ‘He was a tall, lean man with square shoulders but one thing that made him so recognisable from his team mates was that he always wore the jersey outside the togs, be it black and amber or white with a green sash, and strange to say it always looked well that way on him. His duels with Jimmy Walsh, Carrickshock in Shefflin’s Field at Ballyhale were a treat to behold.’

Another description of him was as follows: ‘Nothing was impossible for Lory Meagher when he was at his peak. Usually a centrefield player does not score often during a hurling game, but this rule did not apply to the hurler from Tullaroan. With long effective strokes, as straight as a bullet out of a gun, he caused the flags to be raised often and fast and, as sure as Easter falls on Sunday, he shook the net with the sliotar when most often needed. Lory was also a hurler who never stooped to ‘dirty’ play and even in the toughest encounters he played, as always, honestly and skillfully. He was a man of slender build without any extra flesh but still he had a great capacity for capturing the sliotar in a tough corner, and as for his speed, Caoilte Mac Ronain of the Fianna would not outpace him.’

In his book, A Lifetime in Hurling, contemporary Tipperary hurler, Tommy Doyle, chose Lory Meagher at centrefield, with Jim Hurley of Cork, in his best fifteen hurlers. He had this to say: ‘Lory Meagher was one of the greatest hurlers Kilkenny ever produced. When the occasion demanded few hurlers could rise to the same brilliancy as the Tullaroan captain, and for a period of ten years or so he inspired his county to many notable triumphs. It is the exception rather than the rule to see midfielders figure high in the scoring list in any match. But Lory Meagher needed only the slightest opening at midfield and he could notch points from the most difficult angles. And, as often as not, his long drives found the net at a vital stage of a championship game. Built on light wiry lines, he was a grand, crisp striker, with a skill and ash style all his own.’

And Padraig Puirseal, already mentioned, had this to say of Lory: ‘He was a slight, lithe young man, with the power of his hurling already in wrist and forearm, an easy grace in his every movement on the field, and a remarkable sense of position and anticipation that made it look as though he could attract the ball to wherever he happened to be. He made hurling expertise look simple.’

‘There was Lory as I remember him first in the days when all the world was young, tall and slight, lithe and lissom, his flashing caman weaving spells around bemused Dubliners on a sunny Maytime Sunday at the Old Barrett’s Park in New Ross, long, long ago. Or memories of Meagher on that same playing field in 1929, playing such hurling in torrential rain that men said afterwards, as they splashed down the hilly road by the Three Bullets Gate, that Lory could talk to the ball and make the ball talk to him.’

On a personal level, I was very young when I first heard the name Lory Meagher and, if I remember correctly, I heard of him as Lory in ‘Over the bar, Lory.’ I always associated him with scoring points and put him in the same league as Jimmy Kennedy, Liam Devaney or Jimmy Doyle. I never did discover very much else about the player until the time the Team of the Century was announced in 1984. It came then as a surprise to find Lory picked at centrefield and only then did I learn it was in that position that he reigned supreme. He was a scoring centrefield player at a time when centrefield play was much more important than today. Because the ball didn’t travel as far as it does today, the puckouts landed in the centre of the field rather than on the forty or further on. To have a player who could catch the puckout and send it over the bar was a major asset to a team. Or. more often, Lory doubled on the ball, sending it on its way to the forward line. He always kept the two hands on the hurley and expounded that theory in training. This is what Lory was capable of doing and it made him unique in his time.

One surprising thing about Lory’s career is the lateness at which he arrived on the scene. Born in 1899, he made his first appearance for Kilkenny against Dublin in the Leinster final of 1924. He would then have been in his twenty-fifth year. Kilkenny lost by 3-4 to 1-3. Lory did not score. He was to turn out for the black and amber until 1937, when he went on as a substitute in the All-Ireland final at Killarney. During his career he won five county finals with Tullaroan, in 1924, 1925, 1930, 1933 and 1934. He won three All-Irelands, in 1932, 1933 and 1935 and was on the losing side in 1926, 1931, 1936 and 1937. He won two Railway Cup medals, in 1927 and 1933.

A curious stroke of fortune marked his introduction to inter-provincial honours and finally set him on the path to hurling fame. It was in the Railway Cup semi-final of 1927 between Leinster and Connacht, played at Portlaoise. He described what happened in a newspaper interview: ‘I was not on the Leinster team but I was brought to Portlaoise by one of the players, who got me a place on the team. I played the game of my life that day. I held my place for the final against Munster on St. Patrick’s Day, but my good friend lost his. Leinster won by 1-11 to 2-6.’ Some might say a small enough return for such a superb talent. Because of his injury in the second game against Cork in 1931 he lost out on selection on the victorious Leinster team in 1932.

One of the reasons proposed for Lory’s late arrival on the inter-county scene was the precarious state of club senior hurling in the years following the Rising. The 1916 championship wasn’t completed until August 24, 1919. The final was played at Knocktopher and Mooncoin defeated Tullaroan by 5-2 to 2-3 in a replay. There was no championship in 1917 and 1918 and these years were combined with the 1916 championship. The championship of 1919 was declared null and void when Tullaroan and Mooncoin could not agree on a venue. There was no championship from 1920 to 1922. The final of the 1923 championship, in which Dicksboro defeated Mooncoin, wasn’t played until October 19, 1924. The final of the 1924 championship was played on March 22, 1925. In an interview Lory stated: ‘I was put on the senior team right away and I won my first county championship in 1924. Since Lory made his first inter-county appearance in the Leinster championship of 1924, played in the same year, it would appear that the player had come to the eyes of the selectors before he won his first county championship. Even so, he was still 25 years old. There is a suggestion that he may have made his first appearance with his club in 1919, in the final of the 1916 championship. Because of the difficulties in running the championship during these years, Lory wouldn’t have got many opportunities to declare his wares until 1923-24. Tullaroan didn’t feature in the 1923 final which was played in October 1924. They were beaten by Mooncoin in the semi-final the previous month. There is also a suggestion that he had a polio attack in the early twenties, which may have halted his hurling development.

As stated above Lory made his debut for the county in the 1924 championship, when Kilkenny lost to Dublin. In 1925 Laois were beaten and Kilkenny lost to Dublin in the Leinster final. The loser’s objection was upheld and Kilkenny went on to contest the All-Ireland semi-final against Galway. The selectors made a decision which turned out to be disastrous. Following Mick Burke's poor display against Dublin they dropped him and recalled John T. Power. The Piltown man had not played since he went on as a substitute for Burke in the 1920 Leinster final. Power at this time was out of hurling for years and was around 43 years of age. He was picked on form shown with the 1904-13 team against the current side in a benefit game for Matt Gargan. Galway scored a decisive 9-4 to 6-0 victory.

Kilkenny hoped that the worm would turn in the 1926 championship. There was great interest in the meeting of Kilkenny and Dublin at New Ross, as a result of the objection of the previous year. Matty Power, a stalwart of Kilkenny hurling, threw in his lot with Dublin as a result of joining the Gardai in 1925. Kilkenny survived by the minimum of margins in a close, exciting game. Lory contributed 1-3 to Kilkenny’s total, his goal coming from a free. After the excitement of this victory the Leinster final against Offaly was a tame affair, which Kilkenny won easily.

Kilkenny had lost to Galway in the 1923 and 1925 semi-finals but they survived on this occasion. (It should have been Munster’s turn to play Galway but, because of the delay in the Munster championship, it fell to Kilkenny to play the Connaght representatives.) It was a game of goals, 6-2 for Kilkenny and 5-1 for Galway. John Roberts got five of Kilkenny’s, the other was got by Wedger Brennan. Lory had a quiet day. The All-Ireland final wasn’t played until October 24 because of the marathon Munster final between Cork and Tipperary. Kilkenny gave a disappointing display and the forwards made little headway. The first half was even enough with Cork holding an interval lead of one point but Kilkenny slumped in the second half, going down to a twelve point defeat on a scoreline of 4-6 to 2-0. Few Kilkenny players performed well. Lory was one of the few exceptions.

The defeat must have been galling for the Meagher family. There were three members on the team. As well as Lory, Willie played in the full-back line and Henry in the full-forward line.

There was little joy in 1927. Easy wins against Laois and Offaly put Kilkenny in confident form going into the Leinster final against Dublin in Croke Park. They had a disastrous first half and were behind by twenty points at the interval. They rallied in the second half but were ten points behind Dublin at the final whistle. As well as Matty Power, a second Kilkenny man, the famous Jim ‘Builder’ Walsh, helped Dublin to victory.

Defeat in the first round was Kilkenny’s lot in 1928. They were beaten by Dublin in the first round. There was dissent in the camp because of a dispute between Dicksboro and Tullaroan. The losers fielded without the Tullaroan players, including Lory. Neither did the team do any training together in preparation for the game and failed to last the pace.

There was some better luck in 1929. Kilkenny found it difficult to beat Meath in the first round, with Jack Duggan and Lory Meagher finding it difficult to get on top at midfield. Kilkenny played Dublin in the Leinster final. There was still dissent in the camp. The Dicksboro club, which had three players on the team and three substitutes, asked their players not to play because they disagreed with the selection committee’s choice. The dispute caused a delay in taking the field. Kilkenny won by 3-5 to 2-6 but Dublin objected on the grounds that Kilkenny were late taking the field. The referee reported that they were seventeen minutes late, but Dublin were also late. The final was declared null and void.

Kilkenny were nominated for the All-Ireland semi-final against Galway at Birr. Whether upset by the Dublin objection or because of overconfidence, or, as suggested by The Kilkenny Journal, that a few of the players were under the influence, Kilkenny produced a lifeless performance. They led at half-time but fell away completely in the second half and were beaten by six points. Lory was mentioned in despatches as one of Kilkenny’s better players.

Kilkenny reached a kind a nadir in their hurling existence in 1930 when they suffered one of their rare championship defeats at the hands of Laois in the Leinster semi-final. Their forwards could make no impression. They led by five points at half-time but Laois stormed back in the second half to win by two points. This defeat, however, was to be an unlikely prelude to a great thirties during which the county was to win four All-Irelands and seven Leinster titles.

In September 1930 Lory Meagher celebrated his thirty-first birthday. Many hurlers of that age would be retiring or, at least, have thoughts in that direction. Had Lory taken that route he would probably have gone down in the history books as another good player from the parish of Tullaroan, but he would have been one of many. He wouldn’t have much to show in the line of achievements. He had a Leinster medal from 1925, won in the boardroom rather than on the field of play. He had another medal from 1926, which was won easily against Offaly. He had another victory in 1929 but no medal to show for it. He had a Railway Cup medal for 1927, although he hadn’t originally been picked to play on the team. He had played in one All-Ireland.

His achievements reflected the state of the game in Kilkenny during the twenties. The county won one All-Ireland, beating Tipperary in 1922. They were beaten in one in 1926 and were beaten in three All-Ireland semi-finals, in 1923, 1925 and 1929. In short five Leinster finals brought one All-Ireland success during the course of the decade. The thirties were to bring a dramatic improvement.

When we think about the thirties we remember the period as Limerick’s greatest hurling era; but during the same decade Kilkenny wrote one of the finest chapters in its hurling history. A glance at the record puts the decade in perspective. In the ten years from 1931 to 1940 Kilkenny played in eight All-Irelands, winning four. After the marathon against Cork in 1931, they won three in the following four years and then lost two on the trot. They came back to win in 1939 and lose in 1940 to finish a glorious period. During the same time Limerick played in five All-Irelands, winning three. Two of these victories were over Kilkenny, and their two defeats were by the same team.

It was in the National League that Limerick reigned supreme. In fact the great Kilkenny-Limerick rivalry may be said to have started with the National League final of 1932/33, which the Noresiders won decisively by 3-8 to 1-3. Following that defeat Limerick were to record five consecutive victories in the competition, while Kilkenny had no further success.

There is no doubt about the dominance of the two teams. Dublin was the only other Leinster team to appear in an All-Ireland, losing in 1934 and winning in 1938. Cork won in 1931 but lost in 1939. Three other Munster teams made it to All-Ireland day: Tipperary did so successfully in 1937, but Clare in 1932 and Waterford in 1938 fell at the final hurdle.

Limerick’s dominance in the National League left meagre pickings for other teams. Cork won twice, and Galway and Dublin each had victories. Tipperary were on the losing end on four occasions.

The thirties is a fascinating period. It seems as if Limerick won the publicity war. The team strides across the decade like a colossus, larger than life and built in the heroic mould.. They are led by a giant named Mackey and at their best they are unstoppable. They excite the public and they are great showmen. They win leagues and All-Irelands and build churches all over the place. They win five of the ten Munster finals, four of them in a row from 1933 to 1936 inclusive.

Kilkenny were less flamboyant. They did things on a quieter note. I suppose the contrast between the personalities of Mick Mackey and Lory Meagher reflects the differences between the teams. While Limerick might have been doing things dramatically, Kilkenny were doing them effectively. And, they were an effective force during the decade, winning eight Leinster titles, - the two that escaped them were lost in replays, - and four All-Irelands. It appears to me as if Kilkenny felt a certain envy at the publicity Limerick drew on themselves. There is a newspaper quotation from 1935 which reflects this feeling. Limerick were favourites for this final, being All-Ireland champions. In a terrific struggle Kilkenny won by a point and were ecstatic. The Kilkenny Post was triumphant. Its headline blared: ‘Limerick forced to acknowledge defeat.’ The report added: ‘Kilkenny’s hurling idols have carried the day. The very laws of nature have been defied. The veterans, the stale champions of 1933, have rocked the Gaelic world to its foundations with an amazing comeback, a glorious and memorable victory. Tradition has been upheld, nay, enriched, a thousand-fold and the children of Clann na nGaedhael worship at the shrine of Kilkenny - the nation’s greatest hurlers.’

So, if Lory’s successes were poor during the twenties, he was to garner a rich harvest during the thirties. Success came in 1931. Kilkenny beat Wexford, Meath and Laois to take the Leinster final. They beat Galway convincingly in the All-Ireland semi-final on a day of wind and rain. Lory gave a star performance.

Cork were the opponents in the final on the first Sunday in September. It was a rousing match which enthralled the spectators. The first half was closely contested, with a goal from ‘Gah’ Aherne helping Cork to a half-time lead of 1-3 to 0-2. Cork stretched the advantage to six points in the second half, but Kilkenny came storming back with a goal and then four points on the trot to take the lead by one point. In the dying moments Eudie Coughlan got possession and made his way towards the goal. As he did so he slipped and fell but struck the ball while he was down on his knees, and it went over the bar for the equalising point.

The replay five weeks later was a superb game and was voted by many the greatest hurling exhibition of all time.. The radio broadcast of the drawn game by P. D. Mehigan had increased interest and swelled the attendance. Cork got off to a great start and led by 2-4 to 1-3 at the break. In the second half Kilkenny drew level and went ahead and again the Leesiders had to get the final score, as on the first day, to level the match at 2-5 each, the equaliser being their only score in the second half.

Even greater interest was generated by the second replay, which became a talking-point throughout the length and breadth of the country. At a meeting of the Central Council it was suggested that the two counties be declared joint champions, but this proposal was defeated by ten votes to six, and November 1 was fixed for the replay.

As it was now November, the crowd was somewhat down on the second game, to thirty-two thousand. Many supporters said they weren’t going to the match because Lory wasn’t playing. When the county board heard this they had Lory appear at the station with hurley and boots the day before the match, even though he had no chance of playing. Some people who were taken in by this ruse never forgave the county board. Kilkenny were severely handicapped. As well as missing their captain, Paddy Larkin and Lory, Dick Morrissey were also out because of injury. Kilkenny kept pace with Cork for about forty minutes of the game but collapsed after that and Cork ran out easy winners, by 5-8 to 3-4.

Dinny Barry Murphy’s comment on these notable tussles was that he thought the second match was the fastest he ever played in. ‘To tell you the truth,’ he said, I was dazed with the speed at which that ball was moved and I found it hard to even think.’ And that came from a man about whom this piece of doggerel was written:

Dinny Barry Murphy, boy,

Great hurler, boy!

He’d take the ball out of your eye, boy,

And he wouldn’t hurt a fly, boy!

Eudie Coughlan, whose contribution on the days was enormous, later stated: ‘Kilkenny were a young team coming along that year. We were old and experienced, nearing the end of our tether if you like. I think that was one of the main reasons that Cork won.’ How right he was! During the remainder of the decade Kilkenny went on to win four All-Irelands, while Cork’s name does not appear once on the roll of champions.

Lory became a national hero during these epic games. He scored three points of the 1-6 in the first game and four points of the 2-5 in the second game. His loss on the third day was incalculable. Padraig Puirseal takes up the story: ‘Lory Meagher did not achieve nationwide renown until Kilkenny and Cork met three times in the famed 1931 final. He starred in the first game, a game featured by patches of brilliant hurling, in which many critics felt that the relatively inexperienced men in black and amber had missed an opportunity of springing a surprise on the seasoned opposition. Even still, after almost half a century, old-time hurling followers go into nostalgic raptures about the first replay when two great teams again finished level. Through a tense, thrilling second half, Meagher was a dominant figure, his ball-control, the style and accuracy of his striking, his uncanny sense of anticipation never more evident.

’That evening and through the ensuing weeks, Lory Meagher’s name rang around Ireland. And then the sad news broke. Because of rib injuries Meagher would be unable to take the field in the second replay. Undaunted, Kilkenny made a brief bid to achieve victory, even without his inspiration. They led Cork for forty minutes but then, as the tide of battle rolled against them, they began to fall away. In the closing stages a Kilkenny player retired injured and all eyes turned towards the bench where the reserves sat, while a wail arose from Noreside supporters: ‘Lory, Lory’, they called and there was the start of an abortive cheer when a becapped figure in black and amber came bounding onto the field.

‘Alas, the spectators quickly realised that the newcomer was not Meagher and I can still see him in my mind’s eye, as I saw him then in his best suit, hunched and bowed on the touchline seat, white-knuckled hands clasped tightly on a hurley, tears running down his cheeks because he could not answer his county’s urgent call.’

Maybe a bit exaggerated, definitely a colour piece of writing with echoes of the dying Cuchulainn breaking through. Exaggerated or not it does appear as if Lory was transformed, as a result of his displays in the drawn game and the first replay, from a Tullaroan and Kilkenny player to one of national stature. After this he was in a super league of heroes, which would include Mick Mackey and Christy Ring. He became a household name and his fame was such that when the Team of the Century was picked, over fifty years later, in 1984, he got more votes than any other player for the centrefield position..

How did Lory’s ribs get broken? I asked Martin White and he thought the question surprising. If he knew he wasn’t prepared to tell me. Obviously the name of the player responsible was known. We should have no problem today with our instant action replay. In an interview with John D, Hickey, Lory had this to say: ‘In that game I hurled for fifty-five minutes with three broken ribs and hardly knew it. The mishap happened under the Hogan Stand when I got possession of the ball and as soon as I did a second Cork man came up to tackle me, charged me and I went down.

‘Dick Grace came over to me and after a while I got up and scored a point from the free that we got for the foul. I continued to the end and despite my injuries, I look back with most pleasure on that match.’

The last sentence is significant. If he looked back ‘with most pleasure on that match’, it must have been because of his display. It satisfied him completely and it made him a hero among his supporters. In that game he reached the peak point of his form and set the seal of greatness on a colourful hurling career.

But, to return to the injury. It happened in the opening minutes of the game. This is confirmed by another statement made by Lory in the above interview: ‘In that game I hurled for fifty-five minutes with three broken ribs and hardly knew it.’ That statement makes his performance all the more amazing.

So, who was the guilty party and was the tackle a deliberate one to take Lory out of the game? The most likely culprits were the Cork midfield pair of Jim Hurley and his partner Micka O’Connell. It has taken me some time to find out the player responsible. There is a code of silence, a kind of omerta, on the subject among those who might know or to whom the information has been passed down. After a lot of digging I’m fairly certain the man was Cork centre-back, Jim O’Regan. The story goes that on their way on to the field O’Regan said to Hurley: ‘We’ve got to do something about Lory.’ He had dazzled them with his play in the first game and was their greatest threat.

There is another significance to this injury. Key players attract close attention from opponents. Sometimes the attention borders on the illegal or spills over into unacceptable behaviour. Lory must have been open to such treatment and yet, with the exception of the incident in the first replay, he does not appear to have suffered many injuries. Martin White told me he wasn’t a marked man, as one might have imagined him to be. And sometimes the treatment of star players is more severe at club level than at intercounty level. In another interview Lory expressed the opinion that in spite of his many strenuous inter-county battles, the hardest games he ever played were in the county championships. ‘In inter-county games,’ he pointed out, you meet the cream of each county’s talent, but in local games you are up against every type of hurler.’ A very revealing statement I would suggest!

The year 1932 was going to bring Lory the kind of reward he deserved and for which he waited so long. Victories over Meath and Laois brought Kilkenny to a Leinster final against Dublin. In a great decider Kilkenny came through by four points and qualified to meet Clare in the All-Ireland final. The Banner were making their first appearance since 1914. With twenty minutes to go Kilkenny led by 3-2 to 0-3, their third goal coming from a sideline cut by Lory, which was finished to the net by Martin White. Clare staged a great rally and reduced the margin to two points. In a last desperate effort Clare launched another attack. Their star forward, Tull Considine, got through and seemed set for a goal but Podge Byrne came out of nowhere, tackled Considine and put him off his shot, which went wide.. In the remaining time Kilkenny got a point to win by a goal. Lory played his best game of the year. Clare took their defeat sportingly and invited the Kilkenny team and officials to their banquet in Barry’s Hotel. Here the players mingled in a friendly atmosphere.

Kilkenny were clear favourites for the All-Ireland in 1933, following their win in the National League final. They qualified for the Leinster final after beating Meath. This game was played at Wexford Park against Dublin and was a remarkable decider. Kilkenny were outpaced and out-manoeuvred in the first half and Dublin led by 5-4 to 2-1 at the interval. The second half was in complete contrast with Kilkenny sweeping all before them. With ten minutes to go the sides were level, the equalising point coming from Lory. However, Dublin went ahead again by a point. Then Kilkenny got a free and the Dublin defenders probably thought Lory would go for a point to level the scores. But Lory, seeing an opening, crashed the ball into the net to take the lead. In the remaining minutes Kilkenny got two more scores to win handsomely by 7-5 to 5-5. In the semi-final at Birr, Galway went into an early lead but two goals from Lory from frees put Kilkenny into the lead by half-time. They eventually won by 5-10 to 3-8 with Lory’s contribution outstanding.

The All-Ireland final was a repeat of the league final and Limerick were determined to reverse that result. The biggest crowd (45,176) up to then to see a hurling or a football All-Ireland, packed Croke Park. The gates were locked long before the game started and thousands more were left outside. The game was played at a breathless pace, full of grimness and determination. It was very close, with the sides locked at four points each at the interval. The game remained close in the second half until a goal by Johnny Dunne put light between the teams for the first time and gave Kilkenny victory by 1-7 to 0-6. Lory was not as prominent as usual and scored a point. It was a great victory for Kilkenny but particularly for their magnificent defence.

There was a check to the forward march of Kilkenny hurling in 1934. They beat Laois in the first round and then went on a six weeks tour of the USA. Lory’s name had gone before him and he got the headlines, as the newspapers cashed in on his fame to generate publicity. There is one story told of Lory during his time on the tour. The party were at Coney Island one day and amongst a host of attractions there was a chap on the beach with buckets of golf balls and drivers. Customers teed up and belted balls to sea. Closely woven nets were spread out over a 200 yard X 100 yard area out to sea and you paid your fee and belted balls towards the horizon. Lory, among others, was curious and lined up. He never had a golf club in his hand before. After he had hit a dozen balls well beyond the limit of the nets the guy turned to him and said: ‘So, you’re a professional - where do you play?’ It’s not recorded if Lory replied: ‘Tullaroan.’

Kilkenny came back to the Leinster final against Dublin. It was another sensational game. Dublin led by six points at half-time and by eight with five minutes to go. But, with their supporters leaving the field, Kilkenny staged a great rally which yielded three goals to take the lead, Dublin needed a Tommy Treacy point from a free to level. Lory was one of Kilkenny’s heroes on the day. Portlaoise was again the venue for the replay. Kilkenny were very bad in the first half, failing to raise a flag, while Dublin scored 3-3. The hoped-for rally in the second half didn’t materialise and Kilkenny were beaten by six points and failed in their bid to record four Leinster titles in a row. The losers made a tactical error by opting to play against the wind in the first half. It died down after the interval.

The good times for Kilkenny and Lory returned in 1935. Lory was also captain, as a result of Tullaroan’s defeat of Carrickshock in the 1934 final. It was his fifth county final, the earlier wins coming in 1924, 1925, 1930 and 1933. Offaly were easily beaten in the Leinster semi-final. Laois, who had surprisingly beaten Dublin in the other semi-final, gave a spirited performance for about three-quarters of the final before going down to a superior Kilkenny side. There was an easy victory over Galway in the All-Ireland semi-final at Birr.

It was Kilkenny and Limerick for the All-Ireland final. A record number of 45,591 spectators turned up for the game, which was played in a steady downpour. In spite of the difficult conditions the players served up a magnificent exhibition of hurling, and the match stands out as one of the greatest finals ever played. There was fierce rivalry between these teams by this stage. They had been vying for honours since 1933. They knew one another inside out. They had divided successes and failures. Many of the players had also encountered each other on opposite sides in the Railway Cup. One such set of opponents was Mickey Crosse and Johnny Dunne. The Kilkenny side was expressed in the cant: Why was Mickey Crosse? Answer: When he saw Johnny Dunne! The Limerick version was: Why was Johnny Dunne? When he saw Mickey Crosse! In that encounter in 1935 they tore skelps off each other. A friend of mine who was present at the game as a young fellow, sitting with his father in the Canal End, with a close-up of this intense duel remembers the blood streaming down Mickey Crosse’s face from a blow on the forehead, the whole scene made almost horrific by the rain washing the blood on to the jersey. And, not to be outdone, Johnny Dunne had an injury on the back of his head, which also bled profusely, again exaggerated by the rain. He recalls the only treatment Dunne gave his wound was to drag his cap back over it, to staunch the flow.

Limerick took an early lead but Kilkenny came back and were a point in front at the interval, 1-3 to 1-2. Early in the second half Limerick levelled, but then Kilkenny went in front and had a five-point advantage with fifteen minutes to go. The last quarter was breathtaking as Limerick sought to reduce the lead. A Mick Mackey free was rushed to the net; another point followed and in a welter of excitement during the dying minutes, Limerick fought for another score and Kilkenny defended doggedly. In the end the Noresiders got the verdict by the smallest of margins, 2-5 to 2-4. Tommy Leahy, Lory’s partner at centrefield, got man of the match. He had received good assistance from Lory, who contributed a point to his side’s total, but his overall contribution was impressive. Padraig Puirseal was very impressed: ‘But for me, as for many another, Meagher’s finest hour did not arrive until the final of 1935, in the autumn of his distinguished hurling career. Kilkenny started that day rank outsiders against Limerick, the reigning champions, then on the surge of successes. Hurling fans thronged Croke Park for what promised to be a classic confrontation between the old champions and the new . . . and then the rains came, and in torrents. It was not, one would have thought, a day when a stylist like Meagher could use his unique talents and subtle touches to best effect; yet, if ever he taught a sliotar to obey his every wish, it was on that September Sunday of 1935; he guided that sodden ball over the rain-drenched sod and wherever he willed. His amazing ball-control under such conditions foiled Limerick time and again around midfield, while his shrewd and accurate passes to his forwards forged the second-half winning scores, despite all Mick Mackey’s herculean efforts to cancel them. It was a heart-stopping finish with Lory captaining Kilkenny to one of its greatest victories.’

As captain Lory was presented with the cup. On the following evening he led the victorious Kilkenny team in a victory parade through the city. He was the only Tullaroan man to receive the McCarthy Cup. Two other Tullaroan men captained All-Ireland winning teams before the McCarthy Cup was presented for the first time in the 1923 All-Ireland, Jer Doheny, when Kilkenny won their first All-Ireland in 1904, and Sim Walton, who was the successful captain in 1911 and 1912.

Kilkenny were in great form in the semi-final of the 1936 Leinster championship, beating Dublin by 20 points. In a dogged Leinster final, Laois were overcome and Kilkenny qualified for another tilt with Limerick in the All-Ireland final. A crowd of over fifty thousand, more than was to attend the football All-Ireland, packed into Croke Park on September 6. Limerick determination was at its height. The first half produced a game in keeping with previous clashes, and Limerick had a two point advantage at half-time. In the second half Limerick took over and their superiority was unquestioned. They swept aside the Kilkenny challenge, which could muster only a point in the half, and were in front by 5-6 to 1-5 at the final whistle. Few Kilkenny players added to their reputations.

Lory’s impact on the Kilkenny team had been getting more muted during the previous year. He was picked for the opening games of the 1937 championship. Dublin were beaten in the semi-final and surprise packets, Westmeath, making their first and last appearance in a Leinster final, were overcome in the final minutes of the Leinster final. For the semi-final against Galway at Birr, Lory was among the substitutes, the first time for him to find himself there since 1924. Kilkenny won by a couple of points and qualified to play Tipperary in the final at Killarney. Work had begun in February 1936 on a development in Croke Park which involved the terracing of Hill 16 and the erection of a new double-decker stand to be named in memory of Michael Cusack, but a two-month strike prevented the work being completed by the contract date of August 1937. Killarney was chosen as the alternative venue. Kilkenny were a veteran side but nobody expected their performance to be as poor on the day. For the forty-three thousand who attended, the game could hardly have been worse. It was too one-sided to draw even a decent cheer. From the start Kilkenny were beaten all over the place, and the final score was 3-11 to 0-3 in favour of Tipperary.

Lory came on as a sub, and his appearance was to be his last in the black and amber, the colours he had worn with such distinction since 1924. Although he played his part it was evident that his youthful speed was gone and that age was taking its toll. His arrival may have done nothing to change the direction of the game but he got Kilkenny’s only second-half score. He got a free, tried for a goal as was his wont, and it was saved at the expense of a point. Lory was just two weeks short of his 38th birthday. He must hold the record with Frank Cummins of being the oldest centrefield players to play in an All-Ireland.

Lory retired from hurling after the debacle in Killarney but he never lost his interest in the game, the G.A.A. and, in fact, all things Irish. Looking back on his achievements it might be said he didn’t get the reward his talent deserved. He played in seven All-Irelands and lost four. He should have been good enough for the 1922 team, having been 22 years old at the time. He was probably unfortunate to be in his prime at a time when Kilkenny hurling was unsuccessful. There were ten years between 1922 and 1932 during which Kilkenny went without an All-Ireland success. They were the prime years in Lory’s life. According to Martin White he wasn’t recognised until he was past his prime. Had he lived in the decade from 1903 to 1913 what a difference there would have been!

Where did Lory’s greatness lie? Moondharrig, a contemporary hurling commentator, said of him: ‘Meagher was the stylist of the hurling fields, not alone in the hey-day of his career, the late ‘20’s and early ‘30’s, but possibly in our life-times. Certainly no sweeter striker of the ball has graced the senior championship for Meagher was equally effective off the ground or in the air, from play or from the side-placed ball. Because of the remarkable power that he carried in his forearms, Meagher was a master of the short-swing, the kind of push stroke that we see all too seldom nowadays, when the wide-open all-round swing, which was the hall-mark of what we used to call the ‘five-acre field’ hurler, and which can so easily be hooked from behind seems to have become the accepted practice even among All-Ireland stars.’ Moondharrig continues: ‘Striking a ball from his hand in open ground or from a placed-ball lift, Lory Meagher had the perfect swing and what a pity it is that it was never preserved on film as a model for a new generation.

‘But, especially in the later years of his career, he was a master of the side-line cut, as Clare and Limerick found to their cost in All-Ireland finals. From a touch-line ball out around the 25 yard mark, Meagher was deadly. Once in Waterford nearly forty years ago, I saw him score two goals off line-balls within five minutes, one from the left-hand touch-line and the other from the right, and each time the sliotar flashed to the net off the inside of the far upright.’

Martin White makes the point that he wasn’t a fast man. Like all men who follow horses, he didn’t hurry. He went about centrefield in a canter. He had such a great sense of anticipation that he seemed always to be where the ball was. Actually it was uncanny how he got round centrefield when he seemed never to be straining himself. He had great hands and great strength in the upper portion of his body. He also had a great follow-through. It used to be said of him that he would have made a perfect golfer. On the top of everything he had excellent accuracy.

Asked if Lory would have fitted into today’s game, Martin White has absolutely no doubt. According to him Lory would have fitted into the game at any time and in any place.

One of his outstanding skills was the drop-puck. It was a wonderful stroke. He had the ability to bat down a ball and drop-puck it as it hit the ground. Another tactic was to use it when in trouble. He would throw the ball forward, sometimes illegally, and running after it drop puck it as it reached the ground. The stroke had great direction. It was a favourite stroke of Lory’s at close play.

He had another great talent in overhead striking. He gave a great display of it in the 1931 struggle against Cork. He didn’t catch the ball at centrefield but doubled on it again and again. He was up against Jim Hurley that day, who had inches on Lory and who was another good exponent of the same skill. Despite lacking in the stature of Hurley, Lory came well out of the contest.

Another contemporary recalls: ‘His duels with Jimmy Walsh of Carrickshock in Shefflin’s Field were a treat to behold. It will always stay in my mind of a point scored in one such game. The ball was coming down from a puck-out but in the next instant it was sailing high in the air over the bar at the other end of the field without ever touching the ground, as a result of an overhead connection by Lory.’

Above all, Lory had a quality without which all his skills would have been as naught, and that was a great will to win, a determination never to lose. It was expressed in his willingness to carry on with broken ribs in the replay of 1931. It also found expression in his desire to continue playing into his thirty-eighth year. There are two photographs of Lory which express for me the focus and determination of the man. One was taken at the 1945 Leinster final, showing Lory standing beside goalkeeper, Jimmy Walsh. He’s actually standing in the goals, hands in pocket, cap on head, fag in mouth, completely intent on whatever is happening at the other end of the field. The second picture is of him on a reaper and binder, shirt sleeves rolled up, head bare and fag in mouth, holding the horse in rein and totally rapt in what he is doing.

Despite his quiet demeanour Lory showed outstanding qualities as captain and chairman. These were revealed in the 1931 games with Cork and during the successful year of 1935. Late in his life when he served as chairman of the Tullaroan Club his leadership qualities were shown in his chairman’s addresses and in his words to the players before leaving the dressingroom to play. In his quiet way he could send men on to the field inspired to perform above themselves. He enjoyed a good partnership with club secretary, Danny Brennan. He served for a period on the Leinster Council. Lory was offered a commission is the early days of the Garda Siochana, with a view to encouraging sport in the force. He was also offered a nomination to stand in a general election but turned it down.

During the remainder of his life, Lory devoted his time helping out with club and county teams, and looking after his farm. He was a terribly shy and retiring person, modest and unassuming to a fault. He never sought the limelight, in actual fact shunned any self-publicity with a passion. Nicky Purcell got to know him during his thriteen years as manager of Tullaroan Creamery: ‘Because the Meagher farm practically surrounded the creamery, I often saw Lory at work there. Even in work one could see he was gifted with his hands. Nobody could improve on the way he would cut and lay a fence or plough a field. Everything he did had style and quality about it. At the time I became Manager, Lory’s brother, the late Bill, was a member of the committee and later became chairman. When Bill died, Lory succeeded him on the committee. During his time there he contributed regularly to discussions and was a shrewd judge of situations and problems. Because of this his suggestions and observations were keenly sought and often accepted.

‘In private life I would rate Lory as a reserved and even shy man. To my knowledge he never sought the limelight. I am well aware that he often refused interviews with press men around All-Ireland time. He seemed to be at his happiest strolling down through the fields to the sportsfield on a summer’s evening, enjoying a smoke on his ever-present pipe. At the same time he enjoyed ‘leg pulling’ and was adept at getting the best out of characters like Peter Butler, Mick Dunphy and Liam Kennedy - all of whom sadly have passed away also. All in all I suppose it is fair to say that when Lory died, the game of hurling lost one of its brightest stars, and county Kilkenny and, in particular, his native parish of Tullaroan, lost not only a star hurler but also a highly respected member of its community. It was a pleasure and an enrichment of my life to have known him.’

I asked Martin White was Lory a popular man. He found it a difficult question. Lory wasn’t the type who make popular heroes. He didn’t court popularity. He didn’t put himself in the way of being popular. He did his own thing in a quiet way. I suppose a better word to describe public response to him is to say he was much respected. He had brought honour to parish and county. He had served both well. He had done everything that was asked of him, and oftentimes much more. And, if he were respected at home, he was very much respected outside the county. That respect is best illustrated by two stories. Martin White tells of a meeting between Timmy Ryan of Limerick and Lory many years later. They had played many tough encounters against each other. On this day they met in Dublin and embraced for surely five minutes before getting into animated conversation with one another. Another great opponent was Jim Hurley. When Lory was introduced to Jim’s widow at his funeral, she clasped his right hand in her own and raising her voice said: ‘Oh, Lory Meagher, the most oft repeated player’s name in our house.’

The respect in which he was held was shown in the attendance at his funeral. G.A.A. funerals are powerful affairs but this one was special in the huge number of past players who turned up to pay their final respects. Six of his opponents from Cork in the great 1931 games, including Jack Barrett, Eudie Coughlan, Fox Collins and Jim Regan, asked at his funeral for the privilege of carrying his coffin from the altar to the waiting hearse.

It is an indication of how Lory touched lives through his brilliant hurling skill. But he did more than touch lives. He gave his native place a fame that its size and its importance could never claim. Like the other great stars of the game. Lory lifted his native place on to a higher plain. Anyone who passes through Tullaroan is no longer passing through a quiet village but connecting with Lory Meagher and all the myths an legends associated with his name. Long may his name be remembered.